Why are there cars?

Mobility is a basic human need - for survival. We, specifically the human individual, want to get from A to B.

What do we want at B? The desire, the need for mobility to a location different from the one we are at at a specific point in time derives from very archaic and basic - natural - intentions: we need to hunt for food, be it supermarkets or mammoths, seek shelter, be it a bed or a cave, or we want to socialise with other individuals - which has always been crucial for survival. And of course reproduction.

We have created tools that enable us to get to other places, to transcend space and time. The consumption of physical products, like cars, or immaterial services, be it the phone, social media or apps like tinder makes us socially and physically mobile.

Mobility is apparently the necessary tool for evolutionary survival and process on individual as well as societal level.

Enter: the car.

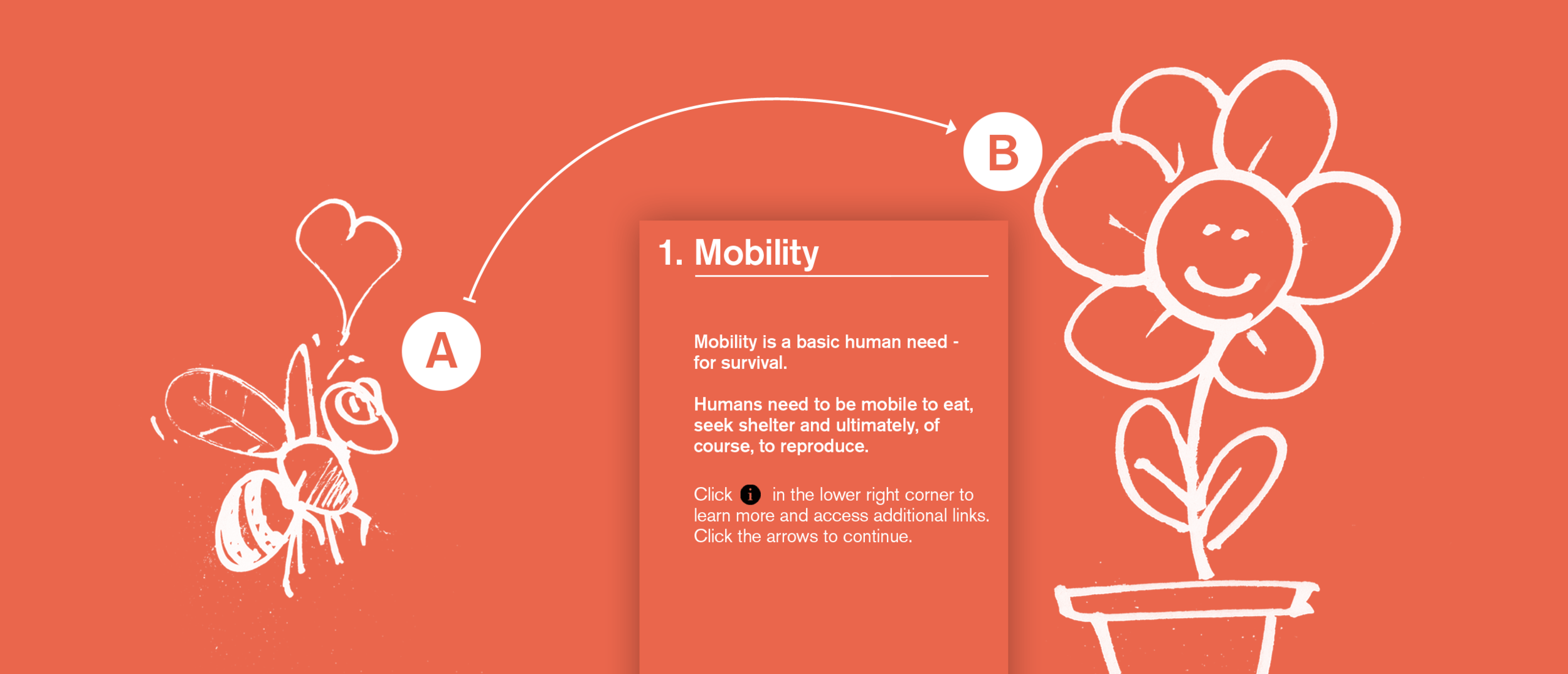

The car and it’s role in mass motorization has naturally been an indicating device, a mirror of society and its sociocultural and technological abilities and expectations throughout the mere dozen of decades it has been around.

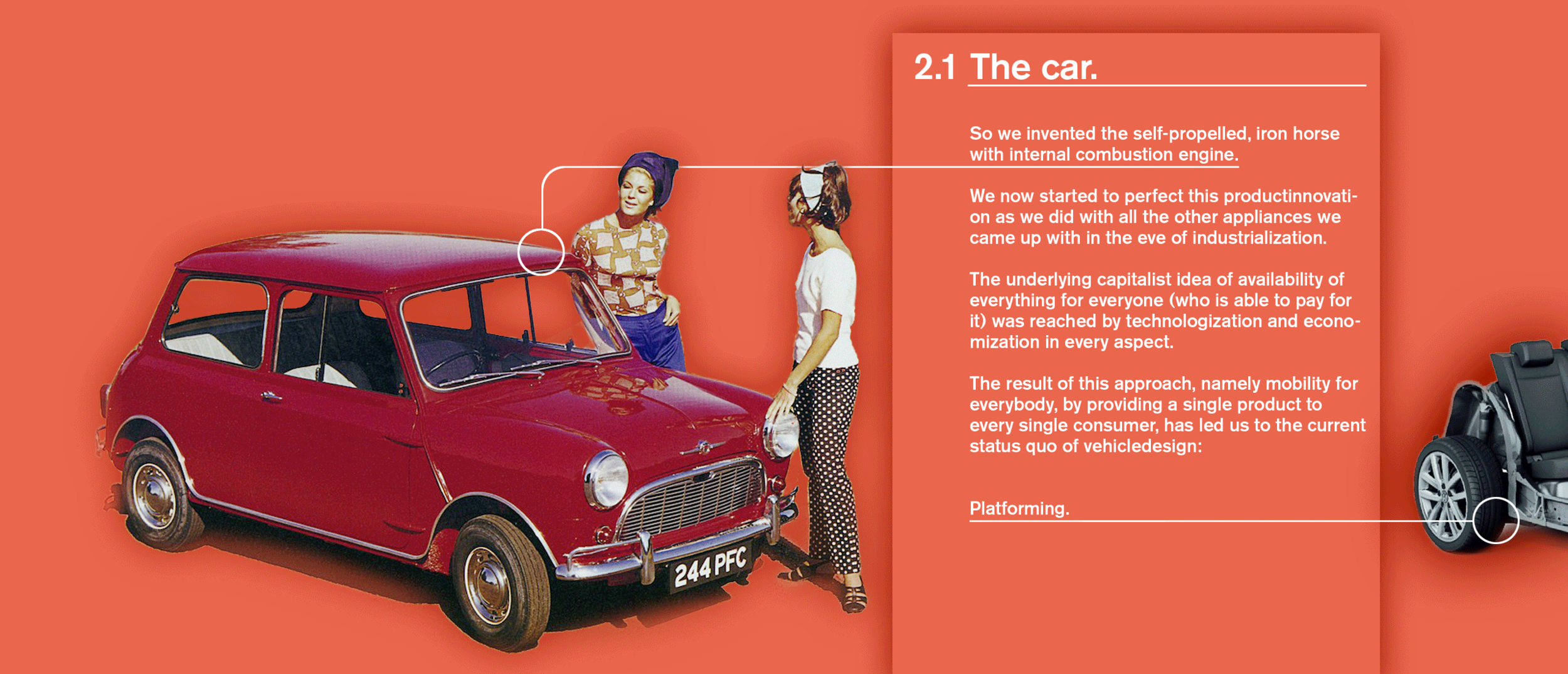

Mini, 1958 - Sir Alec Issigonis - wiki

The first Mini was the product of economical necessities throughout the mass motorization in england overshadowed by the energy crisis sparked during the Suez-conflict. Lower consumption of space, material and cost of production as well as operation were the principles for the development process that resulted in the integral design and engineering achievement that became the iconic Mini Cooper.

Analogously, the Vespa succeeded in answering the existential need for mobility in comparably difficult times, both economically and socially, ten years earlier. As a product of an italian aircraft manufacturer that had to reorient its business due to the demilitarization after World War II, as well as being confronted with a shortage in material and machinery, the Vespa was, like the Mini, a result of strict requirements in a time of reasonable consumption.

The Pragmatism that becomes apparent in this multilateral relationship of how the actual product is manufactured, why it is manufactured in exactly that way, why it consequently looks the way it looks and how all that is rooted in the historic circumstances, is what perfectly describes the qualtity of holistic design that is basically non-existent in contemporary transportation design.

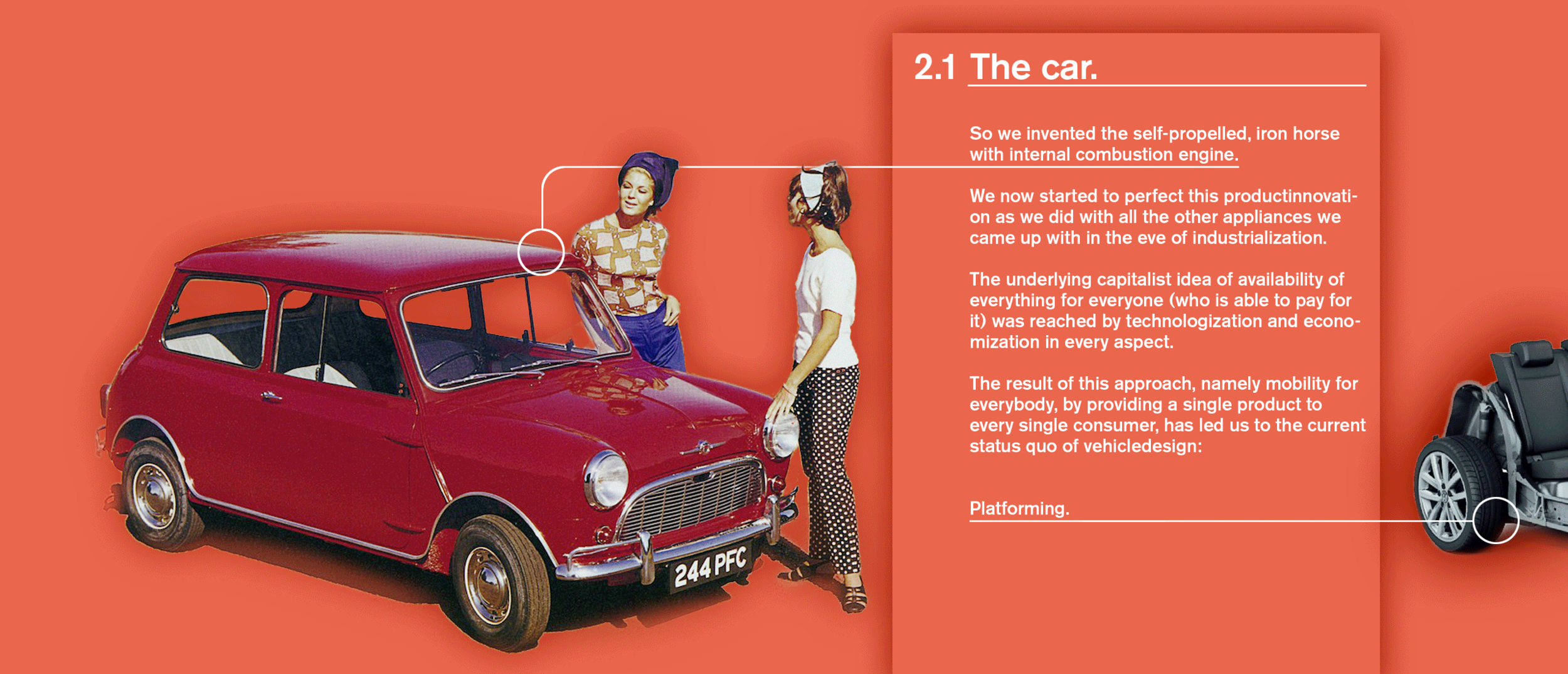

Everybody wants to be mobile, therefore everybody needs his or her own mobilityproduct. Also, everybody is considered individual, as a person, or, currently more importantly, as a consumer.

Our current set of morals in regard to western consumerism and its inherent commercial system are based in our societial realities - mainly revolving around the wealth we have been able to acquire through industrialization and technological progress. Consequently, we end up with a successive development towards an elevation of the individual versus society and the accumulation of material or monetary value as the ultimate precept for personal societal relevance.

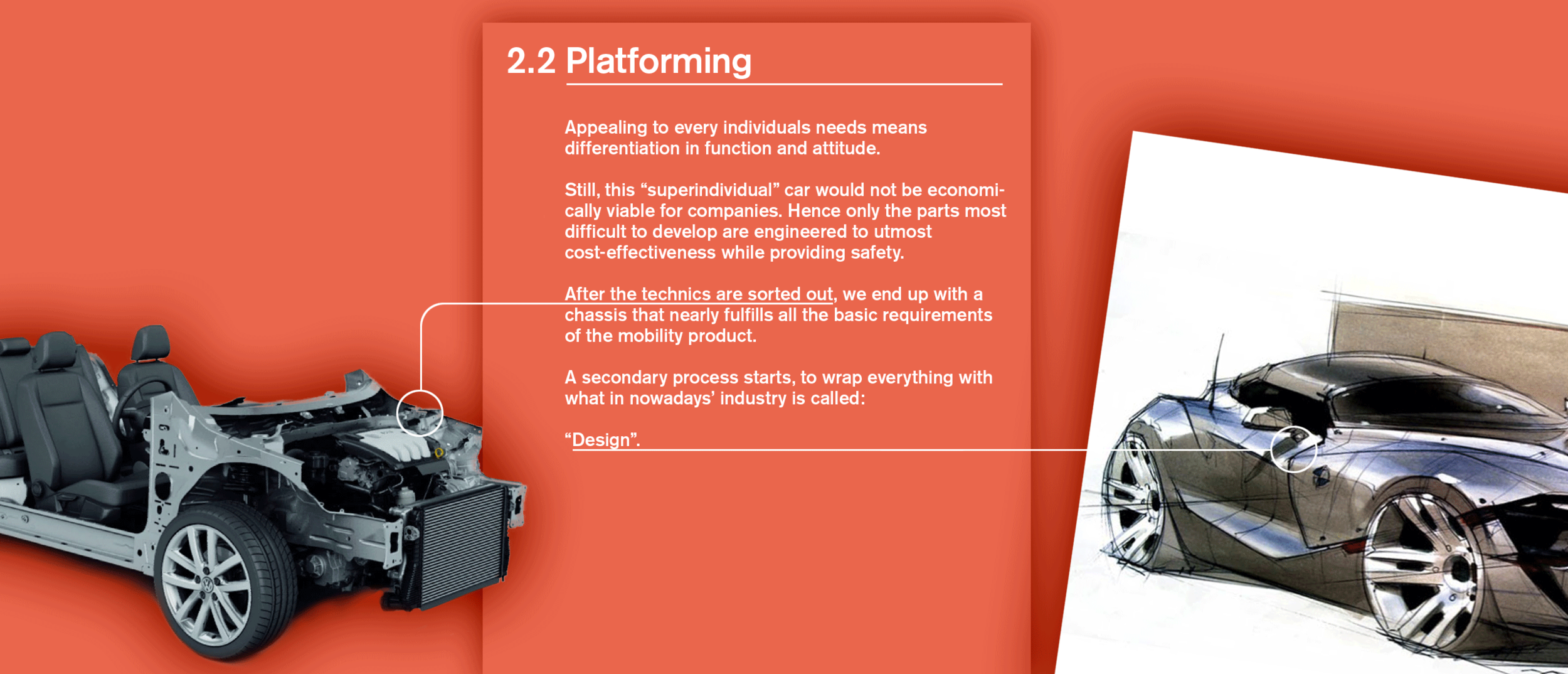

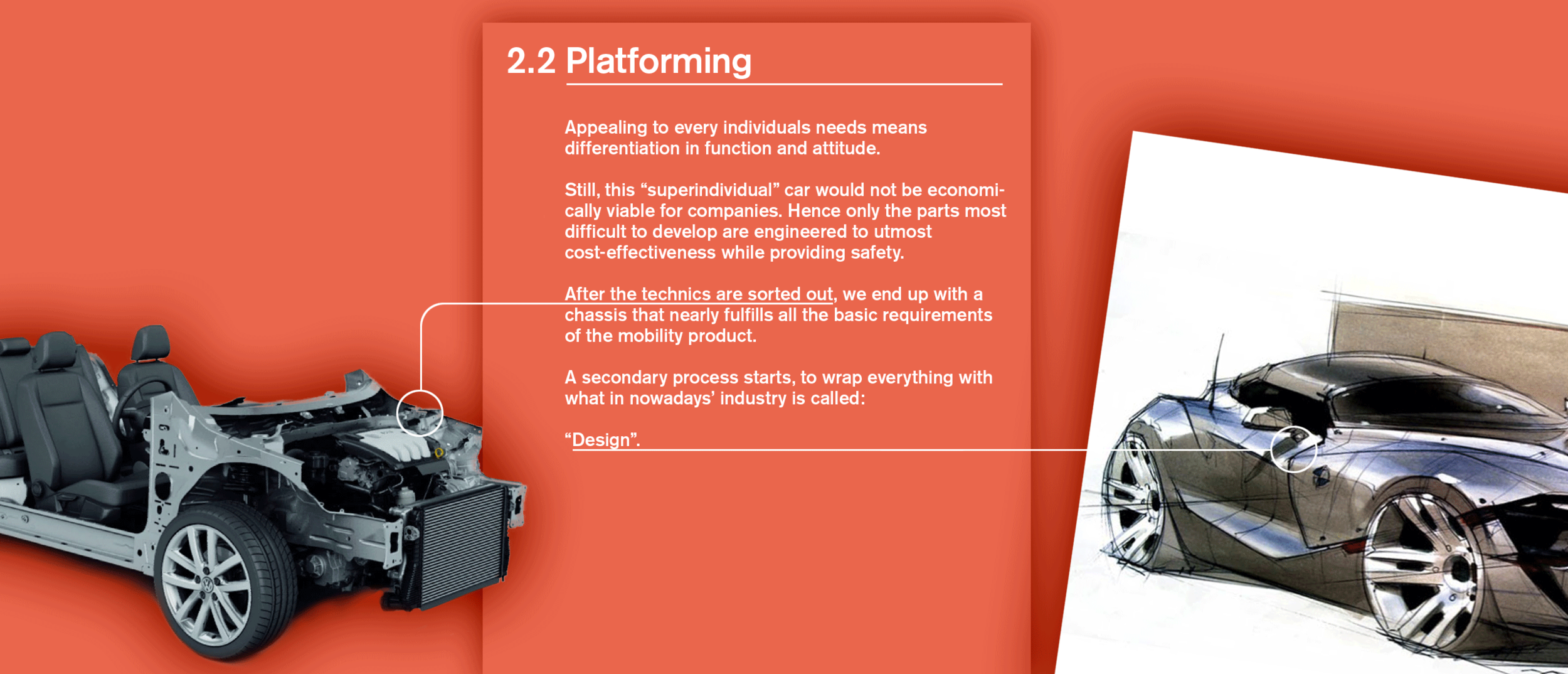

Every individual’s needs and requirements have to be addressed, because the consumerist zeitgeist dictates that they are the most important ones - that means differentiation in function and attitude. Still, this “superindividual” car would not be economically viable for companies - hence only the components most cost and time intensive during the development of the vehicle are engineered to utmost functional and economical perfection while maintaining highest safety standards.

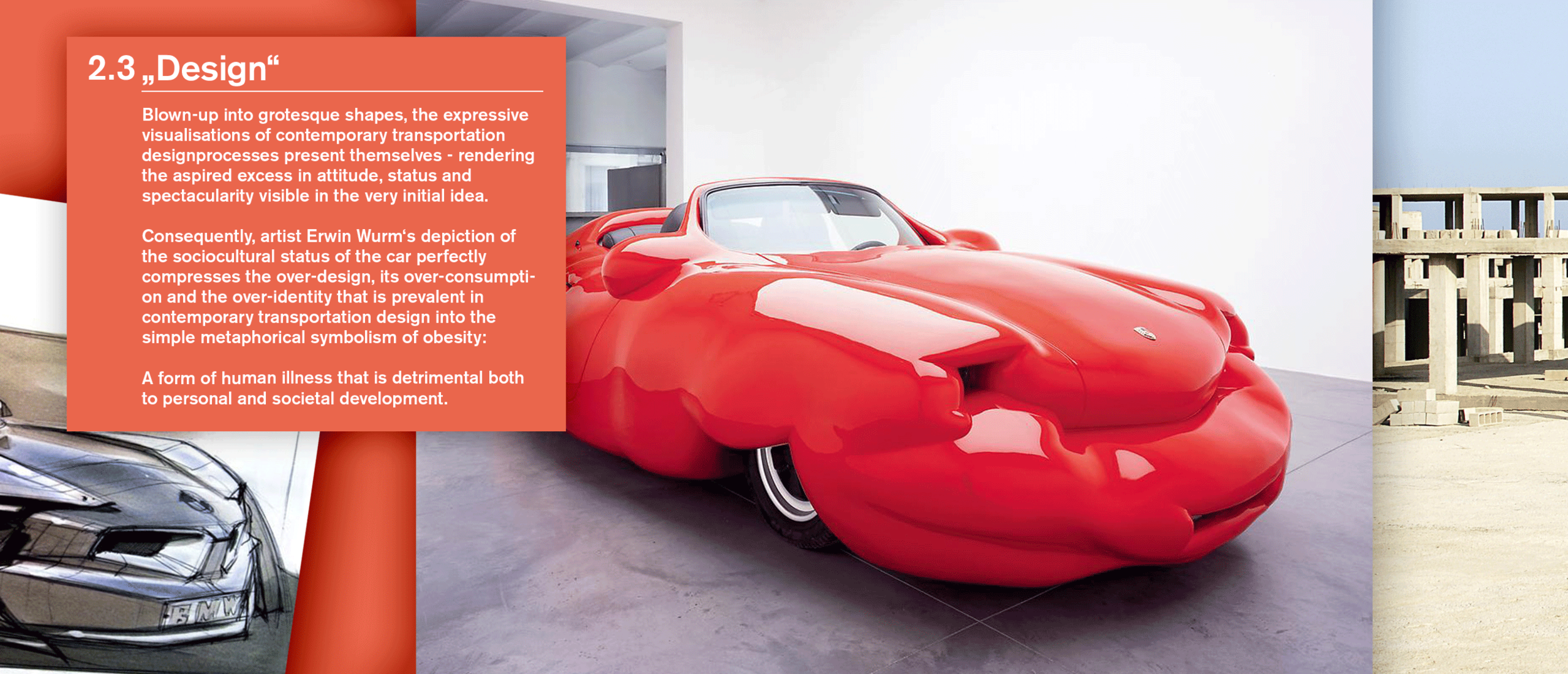

Then, after the technics are sorted out and we end up with a chassis that nearly fulfills all the necessary functional requirements of the mobility product, we start a secondary process from scratch in order to wrap everything with what in nowadays’ industry is called “design”.

This specific approach - Platforming -is not revolutionary at all - AEG and many more did it in the infancy of industrial design. Peter Behrens' Teakettle for AEG is an early example of economization in designcontexts. The heating coil was identically constructed in all products, they were merely differentiated by form and materiality of the kettles and handles to appeal to different visual preferences. This only illustrates how the very antithesis of producing only single pieces made the prevalent historic manufacturing culture obsolete - through the prerequisite economization that is inherent in design.

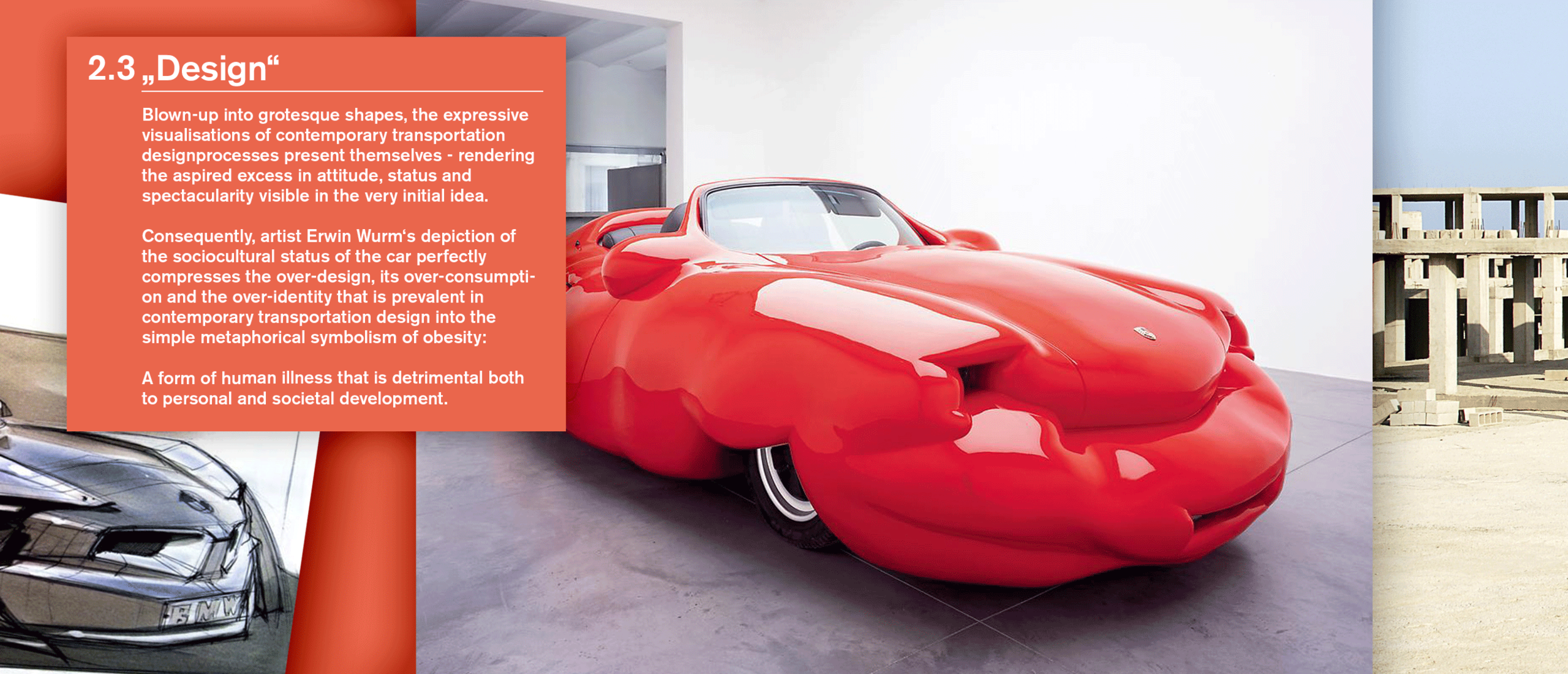

Still, there are two aspects that have evolved to problematic dimensions, because of this very platforming and additive design approach.

Luke Aker - "luxury defined" - The 1996 Maxima GLE Sport Sedan

Videographer Luke Aker filmed his old 1996 Nissan Maxima in his spare time - utilizing all the tricks and techniques used in automotive marketing. Thereby illustrating how quality- and usability promises in overly emotionalised imagery charged up with grotesque bits of pseudohistory become completely disconnected from what is actually presented. Which ultimately renders the discrepancy between visual promise and actual product in the automotive market visible.

Links:

The irresponsible agglomeration of senseless material

The Honda Integra is an extraordinary example of the problematics that evolve when we started to separate engineering and design processes. The Integra is, as of now 5 other motorcycles at Honda, built upon a 700/750cc platform with tubular frame. This platform is then equipped and set up with different seating and storage solutions, covers, wheels, etc. to be able to compete with bikes in the naked, the adventure, cruiser or maxi scooter market. Now the Integra is supposed to be the latter - a large, well-motorized scooter that rivals medium bikes in driving performance, but excels in seating comfort - while sacrificing storage and maneuverability, despite its visual scooter roots.

Being aimed at the hybrid marketsegment of maxi scooters, the inherent compromise of this product becomes visible in its design - or rather Styling - between the scooter and the motorbike. The molded plastic part attempts to imitate the aluminiumcast bridge frame that can be found on high performance bikes - a structural and perfectly engineered part, integral to the bikes functionality.

The plastic part mounted on the Honda Integra only tries to manufacture a “motorcyclish” visual impression, quoting all the semantic values connected to the alu bridge frame, while serving no purpose to the actual function of the product. Calling all this hypocrisy may be a stark statement, but considering, holistically, what the manifestation of this plastic part requires is one step to understand our anachronistic way of designing vehicles, and can be witnessed on basically every vehicle design out there.

First of all, the part adds weight to the vehicle, while serving no functional purpose but to cover the innards of the vehicle. Vehicles nowadays have to be lightweight in order to comply with governmental regulations as to how much carbondioxide their manufacturer’s fleet is allowed to emit. On top of that of course, extra weight needs extra energy - hence adding up to a unnecessary consumption of fossile resources with accordingly climate harming emissions.

The portrayal of functional parts that are not functional makes the design less comprehensible - because what is shown on the outside does not visualize what is happening inside.

This dishonest mode of design ultimately moves form and function apart from each other.

The mere design process of the overall vehicle design takes working time from design development - drawing, prototyping in 2D and 3D, to engineering - CAD, tool construction, simulation, as well as in manufacturing - mounting, quality management. Now, not yet even considering the loops in these processes, the mere cost of producing high precision plastic parts with massive injection molding machines and the necessary investment in factories and material ressources makes it hard to understand why anybody should be inclined to produce a single, senseless, merely hypocritical component for a product with such effort in today’s struggling transportation markets.

Supplying every individual with an individual product for - in this case - mobility, is not a responsible decision, considering the discrepance between available resources like space, material and manufacturing capacities for such a vastly inefficient transport solution.

Still, Apps do not get us to places, physically - the solution is a hybrid one: dynamic use of collectively used vehicles - ranging from public transport to sharing services. This multimodal use needs, in order to become a sustainable solution for democratic mobility, new means of transport and most of all a new set of principles for designing them.

Clean hybrid or electric drive, autonomous vehicles, shared use and everything fueled by energy from sustainable sources - these are to be the ingredients for the „automotive revolution“ - but there‘s far more to a sustainable vehicle than that.

Yet, nearly every existing design only incorporates a few of these aspects. So what if we contemplated the global set of problems at hand with a holistic scale?

What if we took, for instance, globalization, city planning and demographics into account?

what is mobility?